The numbers and reasons for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) are compelling enough: 12 countries that together account for 11 percent of the global population and 40 percent of world GDP. This translates to a population of 800 million with a combined GDP of $28 trillion and 25 percent of global trade value.

Signatories include Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States and Vietnam — an economically diverse bunch of emerging and developed economies on both sides of the Pacific with inherent demand-supply complementaries in agriculture and food. Considering current trade flows and the extent of liberalization to be effected on feed and livestock related goods under the TPP, focus has been on the largest players – Japan and Vietnam as net importers and Australia, Canada and the U.S. as net exporters.

The big picture and deal

As far as trade agreements go, the TPP is a big deal for agriculture. Cards were laid on the table and signatories have agreed to abolish or reduce a range of tariff and non-tariff barriers; accord members with preferential tariff-rate quotas (TRQs); and harmonize regulations on sanitary and phytosanitary issues, among others. Such unprecedented moves would open up lucrative new markets, particularly in Japan whose agriculture sector — second only to the United States within the TPP — remains insular and highly insulated through decades of protectionist measures. New provisions have also been made to level the playing field for state-owned enterprises that enjoy implicit national benefits, a first for any free-trade area (FTA).

Liberalizing trade under the TPP is seen to strengthen existing trade relationships and open up new benefits for trade partners with no prior FTAs such as between Canada and Asian members, while keeping competition from non-TPP feed commodity and animal producers at bay.

Tariffs and trade barriers notwithstanding, TPP countries are already important agricultural trade partners of each other. U.S. soybeans already enjoy a 45 percent, 55 percent and a whopping 95 percent import share in Vietnam, Malaysia and Japan, respectively. Canada and Australia have captured wheat export markets in these countries while the latter and New Zealand dairy products have a strong foothold in Vietnam and Malaysia. Meat products from Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States are also well entrenched in these markets.

Animal feed gains

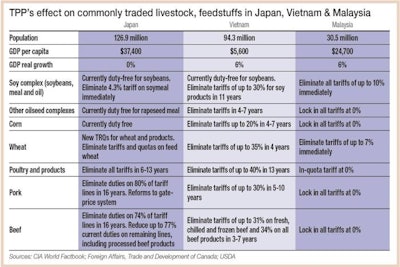

Under the TPP, imports of corn, soybean and meal, other feed grains and oilseeds will see immediate or gradual tariff eliminations over time. In Vietnam, soymeal importers face a range of tariffs under the country’s various FTAs. Corn and soybeans are duty-free.

Given feed production trends and existing tariff structures, Vietnam’s corn, soybean and meal imports have grown 30, 21 and 14 percent respectively between 2013 and 2014, fueled by booming demand growth from the livestock and aquaculture industries and domestic raw material shortages.

In January 2015, Vietnam abolished its 5 percent VAT on feed ingredients. Further TPP tariff reductions would lower the cost of procuring feed and partially offset the challenges commercial livestock producers face from lower priced meat imports, particularly for poultry.

Some gains in Vietnam could be expected for U.S. soymeal through capturing a share of increased feed demand and possible trade diversion away from Argentine, Brazilian and Indian sources. Australia will likely remain the dominant supplier for feed wheat to Vietnam.

Heavily reliant on imports for feed production, Japan buys up to 90 percent of feed corn and close to all its soybeans for crush at low to no import tariff. Despite stagnating demand and a sluggish economy, the country boosts developed world consumption volumes, with annual feed production at about 24 million metric tons.

At present, vegetable protein meals are imported duty-free. Scrapping duties on imported soybeans could boost the domestic crushing industry through lower prices, although this would depend on soy oil demand and domestic crush profitability relative to imports. The current dominance of U.S. soybeans and Canadian rapeseed (food and feed), at two-thirds and above 90 percent of Japan’s market share, respectively, will likely hold steady if not strengthened with the TPP.

Meaty matters

Fresh and processed meat product exporters stand to be among the top gainers among TPP exporters, conferring indirect benefits to domestic feed industries. Estimates from a Global Trade Analysis Project model have put expansion from intra-TPP trade in meat at 43 percent of the total increase in agricultural trade from 2014 to 2025.

Much of these gains can be attributed to Japan, which agreed to slash its notoriously high tariffs on fresh, chilled, frozen and processed meat products within 15 years, and reform its pork pricing system. Import tariffs on beef currently run up to 38.5 percent while a gate-price system for pork that imposes a minimum “reference” price and added duties on imports make pork prices in Japan among the highest in the world.

Considering that the prohibitive tariffs and quotas still stand for non-TPP countries, TPP exporters would gain a huge and exclusive advantage. In fact, about 68 percent of the potential increase in intra-TPP agricultural trade would come from Japan, particularly from the opening up of its animal product markets.

Feedlot cattle producers in Australia, Canada and the United States stand to gain the most, as will TPP pork and poultry exporters. Chile and Mexico, both of which have seen exports to Japan increase over the years, are also contenders for the Japanese pork market given their FMD-free status, with Mexico already exporting some beef to Japan.

Growth within Vietnamese feed sector

The negative impact on Vietnam’s livestock sector owing to lower-priced meat imports is not expected to dampen feed demand greatly. Affected farms are likely to be family run, small holdings characterized by minimal feed inputs and low productivity. While meat imports, particularly for poultry, will displace many local suppliers, the commercial livestock sector will continue to grow in tandem with the country’s economic growth and rising consumer confidence.

Despite fierce competition among animal feed companies, domestic feed manufacturing capacity is expected to increase by 10 percent in 2015 compared to 2014 while the compound feed industry has been growing at 13 percent to 15 percent annually. Foreign direct investment flows through the TPP are expected to boost Vietnam’s manufacturing capacities.

Foreign-invested feed companies currently account for over two-thirds of current feed output in Vietnam.

More to come?

Closely watched by trade observers everywhere, the TPP may have its own sights on expansion. China’s membership for instance would be a rising tsunami that lifts all boats, or intra-TPP shipments. Thailand and the Philippines have expressed interest in joining the group, and their entry would no doubt expand the global reach of feed growers and manufacturers.

Ahead of any ratification of the 12-party agreement, it remains to be seen how the TPP would really work out in practice. Economic gains aside, contentious issues such as the displacement of small-scale livestock farmers and millers by multinational conglomerates and changes in the agricultural and social landscape as a result, would have to be deftly managed on the domestic political front. Teething problems working with a diverse group on such a scale are also not unthinkable; how these could be tackled would be a matter of legislative and diplomatic dexterity. Governments and indeed the feed world, both within and outside of TPP, will be watching.

Delegates from the TPP member countries met in Sydney, Australia, to discuss details of the trade agreement. From left to right: Permanent Secretary of Brunei Dato Lim Jock Hoi; Canadian Minister of International Trade Ed Fast; Chilean Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Andres Rebelledo; Japanese Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy Akira Amara; Malaysian Minister for International Trade and Industry YB Dato Sri Mustapa Mohamed; Australian Minister for Trade and Investment Andrew Robb; U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman; Mexican Secretary of Economy Ildefonso Guarjardo; New Zealand Minister for Trade and Industry Tim Groser; Peruvian Chief Negotiator Jose Luis Castillo; Singaporean Minister for Trade and Industry Hng Kiang Lim; Vietnamese Deputy Minister of Industry and Trade Tran Quoc Khanh | Australian Minister for Trade and Investment