In the post-antibiotic era we experience today, the key concept in feeding all young farm animals remains “gut health.” With that, we usually imply improving gut health in an effort to negate the need for antibiotics, either for growth promotion or even for prophylaxis and therapy. In fact, there is a recent trend to avoid using antibiotics even when animals get sick, in which case maintaining animals’ health becomes even more important than having them perform efficiently. Thus, gut health remains the focus of much research and commercial effort worldwide.

What we tend to forget, however, is that we often create unnecessary gut distress by feeding the wrong diet, or rather by using the wrong ingredients. Such is the case when ingredients cause either outright increased oxidative stress or inflammation that also leads to oxidative stress. The latter case is difficult to appreciate, but ingredients that induce inflammation also lead indirectly to oxidative stress, which creates a vicious cycle where oxidation causes more inflammation and so on. At the end, gut inflammation from dietary causes can be as damaging as inflammation caused by chronic subclinical infections by pathogens. This is because the result is the same: loss of appetite, gut infrastructure damage, reduced performance, diarrhea, and even death due to secondary complications from opportunistic microorganisms.

To this end, it is important to recognize which ingredients, or types of ingredients, can cause the most damage, in terms of gut inflammation. Here, we will focus on two major sources of this distress, namely the sources of lipids (fats and oils) and vegetable proteins. The first group increases oxidative stress from the onset, whereas the second group leads to autoimmune allergenic reactions causing oxidative stress through chronic gut inflammation.

Sources of lipids

The most obvious source of lipids is that of straight oils and fats we usually add in diets for young animals to enhance dietary energy concentration. We cannot easily avoid doing this because such animals are always in an energy-deficient state. Most common sources of lipids include soybean oil and rendered animal fat (lard, tallow, grease). Such oils and fats are usually protected by the inclusion of antioxidants during manufacturing and feed preparation. In fact, even vitamin E is required at higher levels when high-lipid diets are used. The problem with such products is that they can easily become rancid, releasing free radicals (oxygen atoms with unpaired electrons that scavenge electrons from other useful molecules, such as DNA). In lay terms, free radicals can be envisioned as internal toxins. The organism has many mechanisms to counteract the harmful effects of free radicals, but when it is overloaded or compromised, then oxidative stress ensues. In an animal that already suffers from low gut health status, such oxidative stress can easily lead to further complications. The problem of rancidity is not a light one; feed manufacturers selling to countries that otherwise enjoy a hot and humid climate are known to have withdrawn from the practice of using straight lipids from sensitive diets. This is because customers often complain about animals that refuse to eat rancid feeds during the summer.

Animal-derived ingredients are also a good source of lipids prone to rapid oxidation, under adverse conditions and without antioxidant protections. Two examples are very well known cases among nutritionists: Fish meal that contains usually about 10 percent oil is known to suffer from rancidity problems. Usually, this is because fish are not processed soon enough after harvest, allowing natural lipids to begin the process of oxidation, which is auto-catalytic (meaning, once it starts it feeds itself). High-quality fish meal can only become rancid under improper storage condition, just as all high-fat ingredients can spoil likewise, and as such this is not part of the discussion here. Poultry byproduct meal is another lipid-rich ingredient (more than 10 percent) that can become a source of free radicals. Again, protection with an antioxidant during manufacturing ensures a higher-quality product, but such measures always increase cost, something undesirable when an ingredient is favored due to its low cost profile. Of course, all other ingredients including those of vegetable origin can be the source of free radicals, but here we focused on two prominent cases where things can easily go wrong if adequate precautions are not taken, especially when such danger remains largely unrecognized.

Vegetable proteins

When it comes to vegetable proteins, we normally think of soybean meal and its anti-nutritional factors. This is correct, but first, we must note that not only soybeans contain such anti-nutritional factors. Almost all vegetable proteins contain anti-nutritional factors, but not all of them cause gut damage. In fact, the majority of these factors simply reduce digestibility or absorption of other useful nutrients (hence the name). Soybeans, however, are unique in that their proteins are able to trigger an autoimmune reaction, similar to a peanut allergy in humans. This is most prominent to animals previously naive to soybean proteins. Pigs, chicks and calves are all affected to different degrees, and they all react similarly through an acute inflammation response that usually ends up being complicated by natural opportunistic gut pathogens, such as colibacteria, clostridia, coccidia, and even virulent agents.

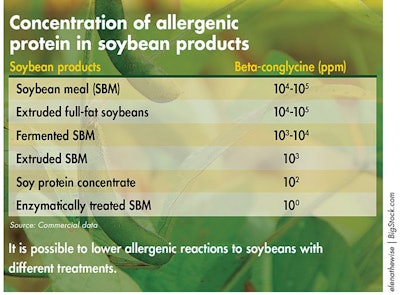

We could avoid feeding normal soybean meal, and this is usually done with high-end feeds, but the cost of alternative, non-allergenic vegetable proteins is usually prohibitive. Other sources of proteins, such as those from animal-derived ingredients, are usually equally expensive, or even undesirable, according to the latest trend in some countries. In the past, a compromise was reached where some part of animal health was sacrificed in exchange for reduced feed cost, and any slack was taken care by the copious use of antibiotics. Today, we can no longer afford to do so, because damaged gut health is not acceptable. Luckily, feeding specialty soybean proteins (see Table 1) reduces or eliminates this damaging allergenic reaction. It is important to note that not all such specialty soy protein products are equally effective, despite claims to the contrary or a high tag price. As with any manufacturing process, product quality remains the final criterion.

In conclusion

Dietary oxidative stress can come from several sources (even some mineral complexes). Oxidative stress causes general system unwellness, leading to reduced performance and health. Oxidative stress can be direct or indirect arising from chronic gut inflammation caused by allergenic soybean proteins. Luckily, treated soybeans can overcome this problem, but always at a higher cost that hopefully guarantees a better product. At the end, it must be remembered that before we start spending money on products that enhance gut health, we must ensure that we do not use ingredients that damage gut health.