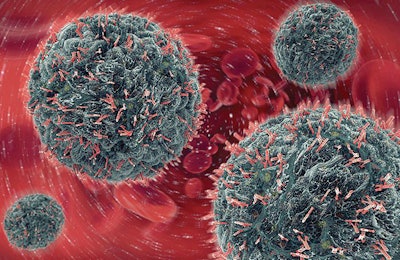

An animal’s immune system utilizes complex regulation mechanisms to achieve three main goals: to recognize any particles or pathogens which are harmful for the body, neutralizing them, and then getting rid of them.

Read the entire report about animal feed and immune response exclusively in the April issue of Feed Strategy.

The innate immune system begins with the skin and mucosa acting as a physical barrier. After this first step, it relies on molecules, such as lysosomes, and phagocytosis cells, such as mast cells. Complex mechanisms will then activate adaptive immune responses — of which inflammation is a natural reaction.

Immunity cells, like T-cells and granulocytes, are produced in the primary lymphoid organs: thymus, bone marrow and, specifically for birds, in bursa fabricus. Those cells migrate to the secondary lymphoid organs, such as gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): mesenteric lymph nodes, isolated lymphoid follicles and Peyer’s patches.

“Immunity actors are quite numerous in an animal’s digestive tract,” said Delphine Le Roux, immunity teacher at École Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort (ENVA), a French veterinary medicine institution.

Because much of the immune system resides in the digestive tract, researchers are increasingly focused on the connection between feed and immunity to gain a better understanding of the ways an animal’s diet may contribute to good health maintenance.

On its first meeting with pathogens, the immune system produces antibodies: mainly IgM (non-specific) and then IgG, which is more efficient.

The first ingestion contributes to young animal’s immunity with, for mammals, colostrum consumption. It must occur less than six hours after the birth. Very rich in cytokines, lymphocytes and antibodies, colostrum’s content depends on the species. In humans and dogs, it is very rich in IgA; in horses, pigs and cats, it is rich in IgG; and in ruminants, IgG1.