With the increasing concerns over antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in human health, the spotlight on antibiotic usage in livestock production requires the industry to prioritize finding alternative ways to treat animals. Bacteriophages are one such technology being researched. These virus-like, natural predators of bacteria were first used to treat infections in people nearly 100 years ago. Bacteriophages could be used to treat bacterial infections in animals and control the spread of pathogens to humans.

Read the entire report about bacteriophages exclusively in the April issue of Feed Strategy.

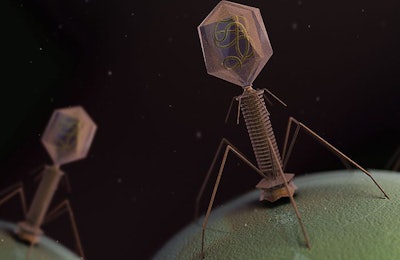

A bacteriophage is a virus that infects and replicates within a bacterium. The name comes from the Greek word phagein, which means “to devour.” Phages are ubiquitous to the environment present within their bacterial hosts, populating spaces such as soil and the intestines of animals.

Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome. They replicate within bacteria by injecting their genome into its cytoplasm. Then, in the case of lytic phages, the bacterial cell is split open and destroyed, enabling the new phage to infect another host. This type of phage is suitable for use as an antibiotic alternative.

The specificity of phages against a particular bacterial species, without negatively effecting beneficial bacteria within the gut, make them attractive anti-bacterial agents.

With the removal of antibiotic growth promoters (AGP), reports suggest increased cases of necrotic enteritis in poultry. The bacterium Clostridium perfringens is responsible for these infections, alongside confounding factors. Scientists identified several lytic bacteriophages specific for this bacterium, demonstrating a reduction in mortality and an increase in weight gain when fed to chicks. A cocktail of C. perfringens phages could therefore be used to help prevent or treat necrotic enteritis.

Bacteriophages have also been used to treat E. coli infections in broilers by injection into the air sacs. In these trials, mortality rates were significantly reduced. Similarly, when bacteriophages were delivered intra-muscularly to chicks challenged with E. coli, mortality was prevented, and no clinical symptoms were seen in the treated birds, compared with 100 percent of the control group.