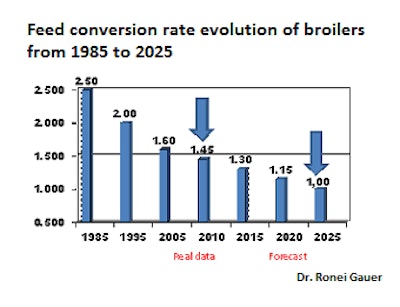

In the recent past, the goal of an average broiler complex was 2:2:42, which meant growing a two kilogram bird (4.4 pounds), with a feed conversion of 2:1, in 42 days. With continued genetic advances, broiler producers will be able to reach that same weight with just one kilogram of feed, probably by 2025.

In a global context, this means we could use 30 percent less grain to produce 100 billion tons of broiler meat, or produce 45 percent more meat with the same feed, making poultry products even more economical and thereby ensuring their availability to a growing population. The critical nature of this is clear; by 2025, the world’s population will be closing in on 8 billion.

Amid our current state, battling $350 per ton feed costs and downward pressure on bird prices pulling profits down, it may be difficult to envision. Poultry operations are already efficient: Reaching two kilogram market weight in 36 days; attaining an 85 percent yield; and achieving a 1.45 feed conversion rate. So where are the gaps between genetic potential and real poultry performance? Is reaching a 1:1 FCR by 2025 a dream or a reality?

The 1:1 FCR was first generated in 2005 (Foulds, J., 2005 The Theoretical Opportunity to Achieve 1:1 FCR). However, the industry is still struggling to reach that target. We estimate that producers are losing as much as 40 points of feed conversion through five barriers, as highlighted at Alltech’s 29th Symposium in May.

Five barriers to improved poultry feed conversion

1. Gut integrity

Gut health plays a vital role in poultry production. Dr. Peter Ferket of North Carolina State University pointed out that only a healthy gut can digest and absorb the maximal amount of nutrients. Three components that are important for a healthy gut and improving FCR include the ecological environment, nutrient balance and symbiotic microbial stability.

Poor intestinal health can increase moisture content of the excreta and therefore negatively affect litter conditions, increase ammonia in the house and lead to more respiratory problems. Wet litter has also been shown to increase footpad dermatitis, hock burns, processing downgrades and condemnations. Runting, stunting and other viral diseases can also be exacerbated by a poor house microflora.

Dr. Steve Collett of the University of Georgia demonstrated the benefits of a program called “Seed, Feed and Weed” in improving gut health and FCR. The program consists of using lactobacillus probiotics in the hatchery to seed the gut, while feeding bioactive yeast carbohydrates and weeding using organic acids in the water and enzymes to reduce non-digestible feed fractions that may cause the proliferation of clostridia. In the absence of antibiotics, a key factor in maintaining an optimal gut microflora is to control the flow of nutrients down the gastrointestinal tract.

2. Feed, water quality and biosecurity

Poor feed quality will always negatively impact intestinal health and overall efficiency of the digestive tract. Feed quality is affected by many factors, including the way the grains and proteins have been grown and processed and the manner in which feed is manufactured. For example, more than 500 types of mycotoxins are known to induce signs of toxicity in the avian species, and it is estimated that 25 percent of the world’s crop production is contaminated.

Dr. Gary Gladys, former CEO of Allen Harim, mentioned that the main component of water management is just making sure your birds are actually getting water. Dr. Aziz Sacranie, Alltech, also spoke on the benefit of good water quality, often overlooked in terms of its impact on bird performance and FCR. Effective chlorination and acidification are essential, given that 70 percent of final bird weight is water. Critical phases for water acidification include the brooding phase, or later in production, when the risk for necrotic enteritis is particularly high.

3. Knowing what you are feeding

Near infrared technology offers the ability to properly determine the actual feeding value of the ingredients in the feed. With current corn and soybean prices at record highs, and easily influenced by market speculations; real time accurate nutrition is at a premium. Gladys and Dr. David Wicker of Fieldale Farms both highlighted the difference between real feeding values and the book values for raw materials. Variations in protein analysis, starch and moisture are just three examples. The FCR losses represented by inaccurate or variable nutritional values can be considerable, and the use of NIR will clearly play a role in capturing value and eliminating losses. Feed materials need to be cleaned, ensuring that both broken grains and dust have been removed from the grains. Enzymes, especially those through solid state fermentation, can also address these variations.

4. Effective coccidiosis control

Coccidiosis control has always been a key concern in poultry farms, but was mentioned by eight of the 10 speakers when discussing FCR, particularly given the growing demands to produce antibiotic free broilers. Any program must address the question of whether to use a chemical, antibiotic or vaccine option. Natural control compounds are arriving in the marketplace, but it seems that natural solutions will involve multiple active ingredients and not a single ingredient. The development of necrotic enteritis is a secondary concern, and the gut microflora management program was demonstrated by Collett and Dr. Mueez Ahmad, Neogen, to be essential.

Diet digestibility could be maximized by ingredient choice and enzyme use, thus avoiding excessive substrate for bacterial growth.

5. Early/In-ovo feeding and programming genes

Studies have indicated that it is possible to imprint the genes of a bird at a very early age and turn it into a more efficient animal later. One way of doing this is through in ovo feeding.

Administration of highly digestible nutrients into the amnion of embryos can bring an improvement in chick quality, increased glycogen reserves, advanced gut development, superior skeletal health, advanced muscle growth, higher body weight gain, improved feed conversion and enhanced immune function. Using nutrigenomic data, almost 30 percent of genes expressed different activity over time by in ovo feeding (Oliveira et. al. 2008).

Dr. Karl Dawson of Alltech presented data showing that limiting nutrient intake post hatch is another way to imprint genes at a very early age. Production traits, such as a tolerance to immunological environmental or oxidative stress and energy and mineral utilization, can be imprinted by adaptive conditioning of gene expression. During the first 24 hours post hatch, the small intestine, liver and pancreas develop at a faster rate than body weight. The chick needs to be fed as soon as possible to provide substrate for gastrointestinal development, weight gain and immune system development. High quality ingredients, mannan-based oligosaccharides, nucleotide-rich ingredients, mycotoxin adsorbents and organically complex minerals can generate significant FCR changes.

Closing the growth gap

Achieving genetic potential is influenced by nutrient quality and analysis, intestinal health, the control of coccidiosis and understanding the influence of nutrition on gene expression. Efficiency is also defined by superior management, and this is a prerequisite for success. If 1:1 is our goal, then we must also ask how much will it cost us to achieve that level of performance, while recognizing as much as 40 points of lost feed conversion can be addressed through interventions available today.