Although soybeans are a major protein source for animal feeds, the European Union has a hard time cultivating this crop, thus running a tremendous deficit that needs to be covered by imports.

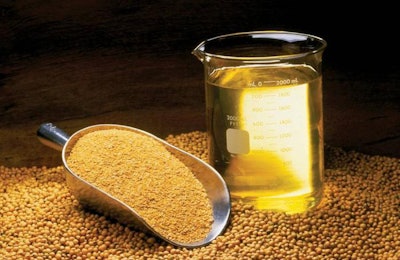

The soybean (Glycine max) is a legume rich in oil (18%) and protein (38%). About 85% of global soybean production is crushed for oil extraction, leaving soybean meal as a major byproduct used in animal feeds. Although the primary reason for cultivating soybeans is oil, the global animal feed industry has become desperately dependent on the protein-rich (44% plus) soybean meal as the primary source of protein for most farm animals.

Today, the three largest producers of soybeans are the United States, Brazil and Argentina which, on a good year, can exceed 80% of total global production. As it is to be expected, these three countries also represent major exporters of soybeans and its products, oil and soybean meal. The European Union runs an animal feed protein deficit covered partly by imports of about 15 million tons of soybeans annually, mainly from the U.S. Recently, it has become a policy priority to reduce EU dependence on soybean imports, especially for animal feeding, giving rise to numerous heavily subsidized initiatives. One of these is the testing of new varieties of soybeans under European conditions, something that remains challenging, at best.

For soybeans to grow profitably, an abundance of sun and moisture is needed. Such are the conditions, for example, in the Midwest region of the United States, where soybeans thrive. It needs to be remembered here that soybeans are believed to have originated in east Asia, where similar (warm and humid) conditions also prevail. As it happens, in Europe, there is the north part, which is humid enough with an abundance of water for irrigation, but, it is also too cold for normal soybeans to grow at maximal yield. Then, there is the south of Europe, which is the exact opposite: plenty of sun and high temperatures, but a real paucity of water and humidity. At the end, this is the basic reason why the European Union cannot grow enough soybeans to compete with cheaper imports.

There are some solutions around this problem, one of which has been testing Canadian soybean varieties that are resistant to cold temperatures. This has been completed with some success in Germany and, if it were to be replicated in the whole European Union, then that could dramatically reduce imports of soybeans. But, this is a rather ambitious goal for EU. Another solution would be to introduce genetically modified/engineered/edited varieties that could enable each region to grow sufficient quantities of soybeans under their own diverse conditions. This is even more improbable because it would require a totally different political approach to the whole issue of genetically altered crops. As it stands now, the EU produces less than 3 million tons of soybeans annually. Genetic companies work hard to improve existing European varieties (more than 500) to be better adapted to local conditions, but this is a lengthy process. Plus, other oil- and protein-rich crops (such as rapeseeds and sunflower seeds) compete with these initiatives.

Despite all good efforts and abundance of money invested in making the European Union feed-protein sufficient, this goal is far from being reached. It is safe to say that “European soybeans” are not the most likely candidate to offer enough feed protein to cover current needs, especially when less expensive imports abound.