In the European Union, it has already become an axiom to reduce crude protein, or rather excess dietary protein while keeping amino acids relatively unchanged and at high levels, in piglet diets without antibiotics. This practice, however, predates the ban on antibiotics. I recall several cases of persistent diarrhea in piglets that were resolved by reducing crude protein, among other measures, when even therapeutic usage of antibiotics failed. This was in the U.S. in the years 2000-2004.

So, in the minds of most nutritionists and veterinarians, cutting back on crude protein is a sure way to control diarrhea, even when antibiotics are used. But, that’s not true in several places around the globe. Let’s talk about Asia, China in particular, where I have had many experiences in the last couple of years. There, and despite the fact that nutritionists and veterinarians recognize the need to reduce crude protein, such measure is virtually impossible for marketing purposes. A low-crude protein feed is considered inferior even though assurances are provided that amino acids are there — so as to protect animal growth. I believe this is a matter of customer education. The same but different is true for the U.S. market that has started the uphill battle against growth-promoting antibiotics. There, nutritionists cannot fathom a piglet diet with only 18 percent crude protein when their existing products contain as much as 24 percent crude protein. Clearly this is a matter of scientific development, and I know they are working hard to this end.

But, let’s consider the existing situation: two large pig markets — the U.S. and China — that cannot accept, yet, lower-crude protein diets for piglets (with or without antibiotics). Is there anything that can be done to ensure that piglets don’t scour and continue to grow when high-protein diets are fed without antibiotics (U.S.) or when antibiotics are not effective (China)? I am using these two countries where I have personal experiences, but the same situation exists in many more places, as I have been told by my professional network.

Fiber in high-protein diets

Let’s look first what happens when we feed excess dietary protein. Basically, it enters the hindgut where it is fermented for energy yielding toxic compounds or becomes bacterial protein, favoring protein-hungry pathogens such as E.coli. End result: diarrhea.

One solution that has been proposed is to counterbalance this influx of excess dietary protein with an excess of dietary fiber. It is known that functional fiber will promote the growth of beneficial bacteria (lactobacteria and bifidobacteria) that will use the excess protein for their growth, instead of burning it for energy, whereas at the same time they will deprive such valuable nutrient from the pathogens. End result: a healthy gut without diarrheas.

At least, this is the theory, and we have enough evidence, both scientific and empirical, to suggest such feed design strategy might provide an alternative to low-protein diets where such diets are not acceptable as of today. But, there are a number of unresolved problems or questions, which failing a clear resolution might cause the opposite result. For example, too much fermentable fiber might actually increase diarrhea — but that’s an entirely other story.

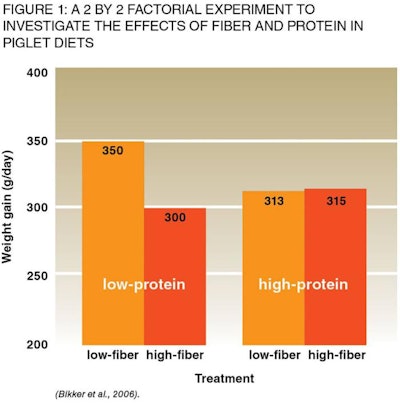

The trial presented in Figure 1 tried to provide some initial insight to the above hypothesis by a clever experimental 2 by 2 factorial design that included a low- and high-crude protein level, combined with a low- or high-crude fiber level. It is evident here that in a low-protein diet, too much fiber is not beneficial. In fact, too much fiber is a negative aspect when animal health is optimal, as evidenced by the low-protein, low-fiber diet that had the best growth performance. When in this diet fiber was added, growth dropped from 350 to 300 grams per day. This is a textbook response! But, that’s old news; modern sources of fibers do not depress performance, as they don’t appear to affect digestibility as much as traditional fibers. This is a very active area of research with some astonishing results.

Why are high-fiber levels not detrimental in high-protein diets? Is it possible to counteract the negative effect of high-protein diets by using a select mix of fibers?

On the other hand, a high-protein diet had reduced growth performance (313 grams per day), something that was to be expected — hence the recommendation to reduce crude protein when not using antibiotics. But, adding an excess of fiber in a high-protein diet did not depress growth (315 grams per day), as we might have expected. Of course, it would have been better if growth was increased, but then research would have been a boring profession. It is my belief, having looked at the experimental diets, that the fiber mix used was sufficient to control pathogenic bacteria growth but not suitable to promote growth of beneficial bacteria. Now, that’s another hypothesis for research to continue.

Type of fiber is important

We tend to group all fibers under one word, but this is an oversimplification. There is a tremendous gap between soluble and insoluble fiber fractions, and clearly we have but only the slightest idea how they influence the microflora balance in the gut. At this point, we go mostly by empirical experiences. For example, I have seen piglet diets that work wonders when sugar beet pulp (highly soluble) is used, even at relatively high levels, whereas in other cases wheat bran (highly insoluble) has similar results at the expense of sugar beet pulp. Perhaps, we need a mix of both, or perhaps we need to reclassify fiber fractions based on their biological rather than chemical or even physiological characteristics. In other words, we need to find those fibers that clearly favor the growth of beneficial bacteria, quantify their effect and translate it into formulation practices. So, research continues!