Producing a quality egg is not only about keeping the customer happy but ensuring that laying hen flocks are profitable. Eggs will be downgraded if they are dirty, cracked or misshapen and therefore command a lower price than eggs for processing. Shell breakage is the cause of 80 to 90 percent of downgraded eggs. The number of cracked eggs will also depend much on the way they are collected, manually or mechanically, and also by which kind of housing system they were produced in.

Shell quality declines as the flock ages and there are more downgrades. The timing of de-population is therefore dependent on the cost of keeping hens vs. the value of eggs they are producing. With genetic advances and investment in cage-free housing systems, producers are looking to extend laying cycles.

In order to ensure profitability, the amount of saleable eggs per hen needs to be maximized. As such, dietary support for hens plays a key role in optimizing egg quality.

Eggshell and contents

Poultry egg shells consist of mostly calcium carbonate plus organic components. These matrix proteins complex with calcium carbonate and make a significant contribution to the crystal growth mechanism and, hence, the structural integrity of the eggshell. A non-calcified organic cuticle covers the shell, offering further protection to the contents. A decline in egg numbers combined with a deterioration in shell quality is the reason for cycles lasting around 72 weeks.

To extend this, nutritionists need to support the tissues and organs involved in egg production.

Eggs display a very consistent composition with regard to proteins, essential amino acids, total lipids, phospholipids, phosphorus, iron, etc. They only differ slightly between breeds and as the bird ages. However, the viscosity of the protein-rich albumen decreases with age – Haugh units decrease on average by 20 over the laying period. This means the antioxidant status of the bird will have a role to play in enabling protein production throughout the cycle. The egg white or albumen is encapsulated in the first of the paired shell membranes and the outer membrane is the foundation for shell formation, both of which require sufficient antioxidant protection.

Pigments are routinely added to laying hen diets to ensure brightly colored egg yolks. They can be synthetic (yellow – apo-ester, red – canthaxanthin or citranaxanthin); nature identical (lutein) or natural (marigold extract). The inclusion of corn in the diet also influences yolk color as it contains the orange pigment zeaxanthin. Access to foliage on the range can also intensify egg yolk color. Regional preferences for color intensity, as well quality assurance scheme guidelines, will dictate the amount and form of pigments added.

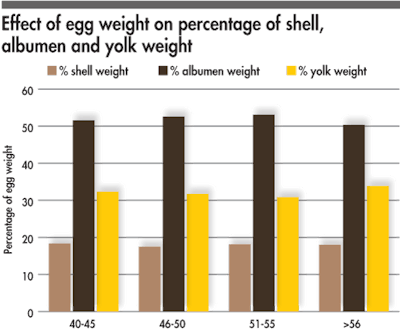

Shell strength decreases over the laying cycle because the percentage of shell weight decreases as egg weight increases. | Sinha et al, 2017

Controlling egg size and number

Influencing egg quality starts before the hen lays her first egg. The aims of diets are uniform pullets that meet target weights for breed and are ready to start laying. However, energy and protein ratio between 11 and 16 weeks is key — as excess energy results in fat birds. As egg weight increases, so the percentage of shell decreases, which is one of the reasons that shell strength decreases over the laying cycle. Similarly as total egg weight increases, so the weight of egg yolk increases. Particularly when increasing cycle length, egg size needs to be controlled to prevent uneconomic levels of downgraded eggs.

Egg size and number can be manipulated with management and nutrition. The heavier the hen is at the onset of lay, then the larger her first eggs will be. Energy and protein levels through the cycle are important to optimize egg production and control body weight, as any excess will result in larger eggs. A hen consuming an extra one gram of protein will lay eggs on average 1.4 grams heavier.

Amino acids, in particular methionine, and linoleic acid levels also increase egg size. If average egg size is increased by one gram, then the total number of eggs produced is reduced by five. Therefore, adapting nutritional specifications can help to control the increase in egg size and hence improve egg shell quality in the later part of the cycle.

Role of micronutrients

A whole article could be dedicated to the influence of micronutrients on egg shell so just key points for each are given below, with calcium, being perhaps the most important influencer of egg quality, given its own section.

- Copper: Essential for normal bone formation and, if lacking in the diet, egg production and shell structure will be negatively affected.

- Zinc: A co-factor in the enzyme that is involved in the formation of calcium carbonate. Shell defects and pigment irregularities are seen if deficient.

- Manganese: Activates enzymes that synthesize some of the components of an egg shell’s organic matrix. Deficiency can result in defects.

Supplying the above nutrients in organic forms improves availability and prevents negative interactions with other nutrients — improvements in both internal and external egg quality are reported.

- Selenium: A powerful antioxidant that when supplied in organic form has been shown to increase the viscosity of egg white and influence egg production. Its influence on ultrastructure development is also reported to improve shell thickness and strength.

- Vitamin D: Controls calcium metabolism and intestinal absorption of calcium. It is therefore essential for egg production and ensuring egg shell quality. Greater bioavailability is seen when supplemented as specific hydroxy metabolites of vitamin D.

- Magnesium: Makes up 0.9 percent of the mineral content of egg shell. Any deficiency reduces egg production and egg shell deposition.

- Phosphorus: Also accounts for 0.9 percent of mineral egg shell. Phytase addition increases phosphorus availability and can help ensure adequate levels for egg production. There is some evidence that hen requirements increase during heat stress, however excessive levels can decrease shell quality

- Salt: Too much or too little negatively affects egg shell quality.

Calcium is essential

Calcium is the major component of eggshell, as well as bone – on average for every egg laid the hen needs 2.2 grams of calcium. Shell weight increases throughout lay; as such, higher calcium levels are needed. However, adequate levels must be provided during rear, transition and throughout lay in order to optimize shell quality.

For satisfactory medullary bone, ovary and oviduct development, calcium levels should be increased (by 1 to 1.5 percent) two to three weeks before the onset of lay. Failure to do this will not only affect the shells of the first eggs, but egg quality throughout the cycle. Once lay is established, calcium requirements increase to 3.5 to 4.5 percent.

The most common source of calcium for layer feeds is calcium carbonate. However, a minimum of 50 percent of the calcium added to the diets should be in the form of large particles (2 to 4 mm). This is particularly important for medullary stores, older birds and those experiencing high temperatures. Fat content of the diet also influences calcium uptake from the diet.

A good egg

Egg producers want hens to deliver a maximum amount of a consistent product that meets the requirements of the packer, processor and consumer. These include integrity of the shell to avoid breakage and contamination, a particular weight, specific color of the egg shell and yolk, and good processing properties reflecting the freshness and expected taste of the egg. Increasing laying cycles will not be profitable unless egg quality can be sustained. Particularly if the concept of “long-life” layers, laying 500 eggs over 100 weeks, is realized. Already the biological limit of one egg per day has been achieved at peak production.

As egg production techniques develop and change, so do the demands of consumers in terms of price and quality. Along with nutrition, genetics and management have important roles to play in ensuring the profitability of the industry. The formulation of pullet and laying hen diets affects egg production, size and quality. They should to reflect the hen’s changing nutrient requirements — controlling egg size and optimizing quality.

References available on request