Availability of alternative protein sources and cost implications need to be considered

Issues such as sustainability, food security and net zero target are driving retailers in Europe to reduce or remove soy from layer diets. While theoretically possible, there are still many hurdles to overcome with regard to the price and availability of alternative protein sources — with the most nutrient-dense diets being the greatest challenge.

Why go soy free?

In Europe in particular, there is a growing pressure to reduce reliance on soy, due to the “food miles” the ingredient travels and the association of South American soy with deforestation. Similarly, sustainability aims have led Western Europe to use more homegrown materials, as well as investigating the nutritional and agronomic challenges of growing more and different protein crops.

There is a very limited supply of European-produced soy. However, for the U.S. where soy can be grown, it is a self-sustaining market with less environmental implications. Food security concerns have been heightened by the pandemic, when sourcing certain raw materials was a challenge, along with significant price rises.

While all these issues are important, Ralph Bishop, nutritionist at Premier Nutrition, suggests asking “what the customers in your country want. This is both the retailers sourcing the eggs and the consumers eating them. Market needs and social pressures will dictate what you do and how much you can spend on changes.”

For example, many U.K. retailers are requesting the use of sustainability certificates including organizations such as the Round Table on Responsible Soy Association (RTRS) that promotes the growth of production, trade, and use of responsible soy. Further, Bishop explains that “in the U.K., net zero targets for agriculture are a hot topic, for which sustainable soy sourcing plays a significant a part.”

Alternative protein sources

There are issues to consider when using more already available alternative protein sources, as well as challenges involved in bringing novel materials on stream.

“Pulses (peas, beans and lupins) can be grown in Europe and have a well-established raw material profile and amino acid specification, but do need slightly different dietary additions. However, the economics and supply chain logistics are different to that of soy, and it may take time to increase availability and reduce costs.”

Oilseeds (canola and sunflower) can be grown in South America and Europe.

“Using both the oil and meals is a big part of the answer for Western Europe to use less soy. We mainly think about Hipro soy, but a lot of soy oil is used in layer diets too. Particularly when using a combination of oilseeds and pulses, it is important to consider the levels of anti-nutritional factors (ANFs),” he said.

However, commercial understanding of ANFs is growing and allowing high levels of certain raw materials when quality control allows. Industry-sponsored research has meant that more canola (rapeseed) is being used in poultry diets by providing maximum levels for each species and age.

Algae is a highly digestible source of protein that requires few inputs.

“It’s likely it will be used first in aqua and pet diets, but it has great potential. As with insect protein, scalability and economics are currently restrictive, but these new agricultural enterprises are developing all the time,” Bishop said.

Insect meal falls under the category of processed animal products, which the EU has recently voted to start the processes of approving for monogastric species.

“Poultry naturally consume insects, and they have a good nutritional profile. Both insects and meat and bone meal (MBM) are mineral rich and using them would have the added benefit of using less mined calcium and phosphorus. The potential of these protein sources could also reduce excretion of nitrogen and phosphorus — another hot environmental topic here in the U.K.”

While in many regions, nutritionists would be surprised at not having MBM available, in the EU, it has been banned since outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in the 1980s and ’90s.

“There is the potential for it to return, feeding pig sources to poultry and vice versa. However, there are some logistical issues to resolve in terms of processing, and questions about exactly what nutritional value the product will have,” he said. “There is a wealth of experience of using the product, but there are challenges for mixed species mills.”

MBM and insect meal have their own inherent environmental benefits in terms of reducing food waste. Less animal waste would end up in landfill or be incinerated; and insects can be fed on certain types of food waste.

“The biggest issue for meat and bone meal in the EU is convincing retailers and the public that it is the way forward in terms of a circular economy,” he said.

Amino acid implications

Layer diets containing increasing levels of alternative protein sources will mean the requirements of added amino acid levels, in order to balance the diet, will change.

“In fact, the current high prices of protein in the U.K. is already making us look closer, ask questions and re-evaluate the use of single amino acids — as they have become more economically attractive,” Bishop said. “Lysine, methionine and threonine are widely used in laying hen diets globally, but the use of isoleucine, valine and tryptophan is growing.”

There is an efficiency gain to using them too: The better the amino acids are balanced, the less protein is wasted, and potential pollutants are reduced.

Production and practical considerations

There are benefits and challenges in using each of the alternative protein sources in terms of maintaining the performance and health of layers.

“It is important to have a robust matrix for the raw materials and have experience of using them under commercial conditions,” Bishop said. “There are lots of people who are using more alternative protein sources, less soy and more single amino acids. The next step is to combine all those principles that we are confident in and move to soya-free diets where required — there are already a few producing certain diets without soy.”

The key to successful reduction in soy use will be change and risk management. “It should be done slowly and in managed stages. This gives both the bird and businesses chance to adapt to the changes,” he said.

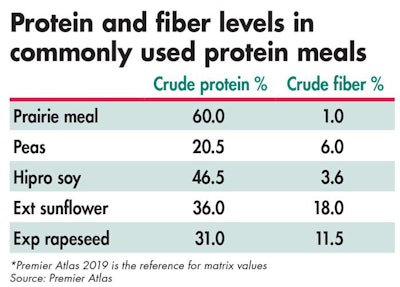

It will also be essential to monitor and maintain gut health, when changing the protein base of the diet in relation to ANFs. Overall, the diet is likely to be higher in fiber, as other vegetable protein sources have a greater fiber content than that of soya. This may be of benefit to laying hens, particularly free range, as feather cover scoring is an important welfare indicator that is used for many quality assurance audits.

Similarly, the much-discussed ban on beak trimming in Europe will require increased monitoring, as well as dietary and management interventions.

Formulation and economics

Adoption of the use of responsible soy, less soy or no soy will all come at a cost.

“The hardest diets to formulate are chick starter and early lay. Both are highly nutrient dense, and taking out soya would also have the greatest cost implications,” Bishop said.

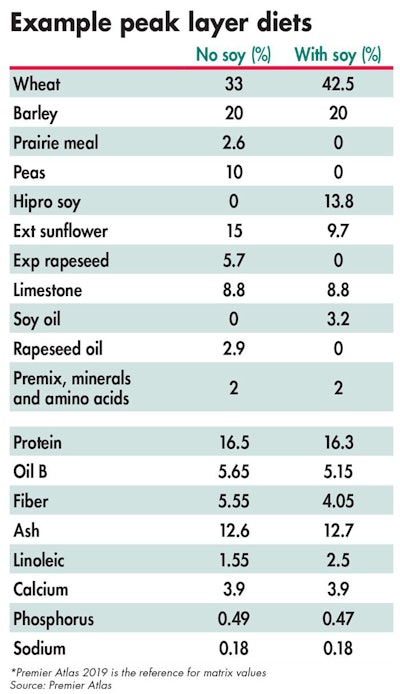

Table 2 gives an example of two peak layer diets: one typical of a commercial ration in the U.K. and the one formulated without soy, utilizing rapeseed, sunflower and more single use amino acids within the premix.

“The question for the industry is what will the consumer is prepared to pay and how much of the cost retailers would absorb — it would not be economically viable for the producers to bear all of the financial burden,” Bishop said. “Also, people need to think not just about the price of, or carbon associated with, a ton of feed. It’s more about efficiency — the financial and environmental cost of producing a kilogram of eggs.”

Study: 87% of emissions in layer production are from feed: https://bit.ly/3gsFNQD