Now that potent products have been developed to replace antibiotics, this is the time to consider the next generation of gut health additives.

For the last 20 years, the scientific community focused on how to replace antibiotics in animal nutrition. I believe we have achieved that with considerable success, especially when we account also for significant advances in animal management, health, and biosecurity.

Nutrition professionals seldom spend time anymore worrying about what additives to use to replace antibiotics. Most of them have made their choices, and they simply watch out for any changes in their production systems that would warrantee a concomitant change in the range of additives they use. Most such additives have already become mere commodities.

The role of antibiotic replacements

Here, it would be wise to remind ourselves why feed-grade antibiotics were used in the first place. It was not to cure bacterial infections, but rather eliminate the loss in nutrient utilization efficiency caused by subclinical forms of disease. More importantly, when used in older animals, antibiotics simply reduced the microbiota load in the gut; less nutrients consumed by bacteria meant more nutrients were available for the animal.

Modern antibiotic replacement products do the same (more or less). Such is the case, for example, with organic acids, zinc and copper products (where allowed and in species that are effective) and, of course, phytogenics. Probiotics offer such an effect as well, but this is either done indirectly or as a side effect.

Next-generation additives

Some considerable, but not enough, attention has been paid to products that enhance the ability of the gut to self-regulate nutrient digestion, immunity and the profile of the microbial population. Here, some products exist, but results remain somewhat foggy because it is so difficult to measure in practical terms such an elusive term as gut health.

But, this is precisely where the future lies, in my opinion, when it comes to next-generation antibiotics. That is, instead of just controlling pathogenic strains of bacteria in the gut by using external products, we can also support the gut to do it by itself. Probiotics and prebiotics are just two quick examples that easily come to mind. And although they require further refinement to achieve such a goal, especially prebiotics, they serve to illustrate the purpose.

In theory, we would be able to continue using antibiotic replacements to control pathogenic bacteria growth in the very first stages of life. In addition, and for long-term use, we would have products that would enable the animal to self-regulate its gut microbiota to its own benefit. Not that infections will be stopped — antibiotics for therapeutic use will still be needed — but with a robust immune system, starting from gut immunity, the animal would not require much additional support. Of course, all advances in non-nutritional interventions should not be abandoned, but rather enhanced.

The ultimate weapon in the battle against pathogens

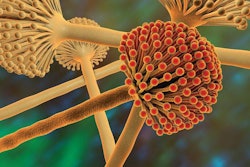

With probiotics, we have had some success in battling pathogenic bacteria. But, this is based on the properties of often alien bacteria (the probiotics) that must colonize the hind section of the gut, and do so under rather hostile conditions. Thus, we need either to allow for a more extended establishment period or very powerful microorganisms. It remains an uphill battle, and the selection of strains is somewhat limited. Both major types of probiotics try to mimic the effect of native beneficial bacteria: To enhance the production of short-chain fatty acids, and especially that of butyric acid (such is the case with local bifidobacteria) or lactic acid (again, the case with local lactobacteria).

In my opinion, always, the ultimate solution would be to find an additive that would empower the local microbiota to work faster and more efficiently. After all, the native species know best how to handle pathogens that harbor the gut (the so-called opportunistic bacteria) or enter through the feed and water.

The problem so far has been that we cannot easily bypass the harsh conditions of the stomach (acidic) and small intestine (alkaline) and the vigorous enzymatic activity throughout the foregut section. Even current additives that target the proximal section of the hindgut (probiotics and butyric acid) need to be protected. This becomes even more difficult when similar products need to reach the distal part of the gut where most pathogens harbor about. In other words, we need to find an effective way to deliver a substantial boost to the beneficial native bacteria at the proximal part of the hindgut. And, this is the current and future challenge in order to build quickly a robust native healthy microbiota population.

How to support the native microbiota

To this end, we must study the needs of the beneficial bacteria. We must also consider the challenges they face. Then we can find out how to feed them better and how to protect them so that they proliferate to the point they can tip the probiotic index to their favor.

This index refers to the ratio of beneficial versus pathogenic strains of bacteria. Naturally, each animal species will have its own idiosyncrasies, but this is just more work for researchers. Nobody said it would easy or fast, but having come so far in the quest for antibiotic replacements, I cannot imagine this next goal cannot be achieved within the next decade.

So far, we have only some prebiotics that work toward this goal, but energy is only one of the needs. And, probiotics can also play a role. In fact, future probiotics may be envisioned so that instead of trying to replace native bacteria, they could work to lend them a helping hand either by feeding them or by protecting them during early development. The possibilities are endless for pro- and prebiotics, and for modified existing additives and new compounds that are yet to be discovered.