Knowing the oil extraction method by which a protein feed ingredient is derived will determine its proper inclusion rate into animal feeds.

Recent trends in human nutrition call for more “cold-pressed” or “natural” oils to be included in our diet. The longevity of this trend remains a matter of speculation, outside the scope of this conversation, but the matter remains in that new feed byproducts become increasingly available. In fact, there is nothing new about these byproducts. The “cakes” of traditional oil extraction methods were the norm in the past and a vast amount of information resides in older textbooks. That does not guarantee, however, that such knowledge is widely available as the internet has supplanted the traditional library.

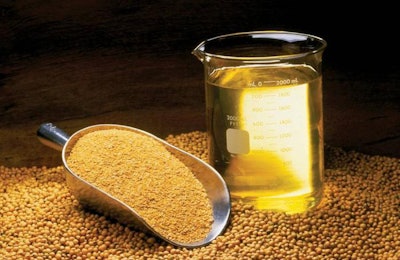

Here we will discuss the three main methods of oil extraction from oil seeds such as soybean and rapeseed, but also linseed, cottonseed, peanut and sunflower because these are of primary interest to the animal feed industry. Nevertheless, the same principles apply to all kinds of more exotic oil-rich sources and their byproducts.

Cold-pressed cake

The oldest practical method of oil extraction still used today is that of mechanical cold pressure, either by hydraulic (least efficient in terms of oil extraction) or screw (more efficient) means. As the name implies, the raw material – either whole or fractured – is pressed without prior heating other than what temperature is generated due to pressure and friction. The resulting oil is as natural as possible retaining all bioactive compounds sensitive to increased temperature, and the taste of the oil remains intact. Cold pressing is relatively cheap, requires simple facilities but extensive labor and can facilitate small enterprises. The resulting byproduct is a caked mass that is fractured into large chunks and sold as such or further milled into a meal-type product and then sold for immediate incorporation into animal feeds. By being inefficient enough, cold pressure can leave up to 10% residual oil. This results in a feed ingredient rich in energy but prone to oxidation, although some of the oil is protected inside the non-ruptured cells. In addition, due to the lack of thermal processing, heat sensitive anti-nutritional factors that remain in the byproduct are not deactivated.

Hot-pressed cake

A more efficient method involves the additional step of pre-heating the raw material, either whole or after coarse grinding. The heated material then is pressed as described above. The increased temperature reduces oil viscosity and increases mash pliability. The heat definitely changes the nature of the extracted oil, but it also helps somewhat deactivate certain anti-nutritional factors. A further variation involves cold-pressing, followed by hot-pressing, yielding two different oil products with the resulting cake being more or less similar to hot-pressed one. In general, hot-pressing leaves about 2% to 4% residual oil in the feed byproduct.

Solvent-extracted meal

Finally, the most frequently used method at industrial scale remains that of solvent extraction. For example, raw material that has been reduced in particle size is preheated and a solvent (such as hexane) is allowed to blend in. The resulting liquid part is heated to allow the hexane to evaporate. The residual meal is also dried, but overheating can reduce its protein quality. Complete removal of the solvent is impractical, but there are norms regarding minimum concentrations. With solvent extraction, the feed byproduct is heated enough to destroy effectively most heat-sensitive anti-nutritional factors. The residual oil however is minimal, usually around 1-2%.

Therefore, next time a feed ingredient such as a linseed byproduct is offered at a competitive price, it is no longer sufficient to inquire about its protein and fiber concentration. Asking also about its oil concentration can reveal much about its processing method, its nutritive value, and of course the level of anti-nutritional factors still present in it. All these will determine the potential maximum level of inclusion in the final animal feed.