Animal welfare standards aim to ensure the mental and physical well-being of livestock is maintained throughout the animal’s life cycle, and span to include the provision of proper nutrition, health, comfort, safety and the ability to express behaviors innate to the species.

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), “Good animal welfare requires disease prevention and veterinary treatment, appropriate shelter, management, nutrition, humane handling and humane slaughter.”

For more than a decade, pressure from the public and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) has driven new regulations and prompted producers to alter production systems to improve animal welfare, taking measures to reduce restricted movement (sows, crates; hens, cages) and crowded sheds (free range); and ushering in an increased interest in slow-growing broiler strains to counter the ill effects of genetic selection.

In turn, meat and egg marketers have used such labels to differentiate their products at the grocery store.

Beyond the positive aspects of animal welfare ideology, in practice, it can pose feeding challenges for livestock producers and feed formulators. The following explores the nutrition pitfalls of new production systems and examines the role nutritionists play in adapting formulations to maintain animal health and performance.

Feeding challenges

As production modifications are mandated, new feeding and health challenges become more prevalent, i.e. difficulties maintaining feed consumption, monitoring supplementary nutrient intake and formulating a higher-energy diet.

“One of the most important feeding challenges posed by new animal welfare-focused production is to ensure adapted diets fulfill the [animal’s] metabolic needs and guarantee profitability to the farmer,” says Alain Riggi, global species manager – swine, Phileo Lesaffre Animal Care.

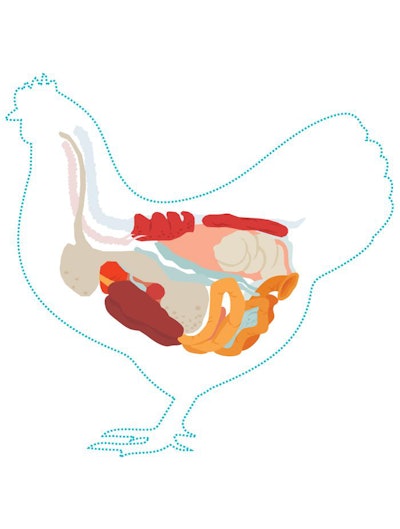

For example, new housing systems affect the energy partitioning of birds due to increased physical activity, notes Silvateam’s technical manager, Nicola Panciroli.

“Although the impact on feed intake and performance may not always be substantial, [new housing systems] give rise to other concerns that could affect bird health and productivity — such as ammonia emissions from the manure, risks of bone fractures due to flying, higher risks for diseases,” he says.

While proper diet formulation is a major concern, disease prevention and immune support in a reduced or antibiotic-free production scheme is, arguably, a more pressing issue.

“Producers are faced with the challenge to exclude antibiotics while maintaining productive parameters to allow for the farm’s profitability,” Carlos Domenech, general manager, BioVet SA.

Antibiotic-free production

What can producers do to maintain animal health and welfare in an ever-changing production environment without (or with reduced) antibiotics usage? The answer lies in the gut.

“The formulation of diets for their specific effect on gut health is becoming a reality in the monogastric animal industries,” Panciroli says. “The maintenance or enhancement of gut health is essential for the welfare and productivity of animals when antibiotics are not allowed in feed.”

To ensure animal welfare is not compromised in an antibiotic-free production environment, gut health needs to be closely monitored.

“Management practices need to be clearly understood across the entire production team. All individuals know how to properly monitor for gut health issues and what to do if — and when — antibiotic treatment needs to be implemented,” says Tom Marsteller, Kemin Industries’ technical service manager – swine.

Though there is no silver bullet to replace antibiotics, nutritionists are focusing on building immunity as the first line of defense.

Gut health promotion

With 70 percent of an animal’s immunity concentrated in the gut, fostering a strong gastrointestinal system will improve its health, performance and welfare.

A healthy monogastric gut maintains homeostasis, prevents infectious diseases, and provides energy and immunity. In contrast, poor gut health can lead to sub-clinical issues — or clinical disease outbreaks — that cause physiological stress to the animal and result in reduced performance and welfare, says Aart Mateboer, business unit director – animal nutrition, DuPont Industrial Biosciences.

“Everything in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is connected: the nutrition, the microbiome and the gut and immune function,” says Mateboer, referring to this interaction as “nutribiosis.”

“This balance is fragile and can be disturbed by animal welfare practices, as well as a wide range of external factors such as climate, environment or microbial challenges,” he says.

Mateboer suggests the right combination of additives and nutrients achieve this balance.

“Optimal gastrointestinal functionality is of the utmost importance because it positively influences animal health, performance, environment and welfare by preventing loss in feed efficiency and the use of antibiotics,” Panciroli says, noting that for this reason the use of feed supplements, functional foods and ingredients have been on the rise.

According to Marstellar, feed additive solutions used to support gut health include organic acids, medium-chain fatty acids, essential oils, probiotics, prebiotics, minerals and beta glucans.

Feed additives solutions

Here are several examples of how feed additives can be utilized to support animal welfare while improving gut health:

- Protease + adaptive direct-fed microbial: This combination works to improve gut barrier strength through tight junctions, enhance protein digestibility, amino acid utilization and fiber-bound nutrient release — as well as positively affect microbiome function. Studies show improved liveability, average daily gain and feed conversion ratio in grower/finisher pigs.

- Phytase: Phytate binds protein in the upper GIT, making it unavailable to the animal, resulting in increased acid and pepsin production in the stomach. As the stomach empties, increased acidity damages the gut absorptive surface and requires more buffering through the release of sodium bicarbonate, negatively effecting gut function. Phytase breaks it down before it binds to the protein, avoiding the anti-nutritive effects of phytate and improving nutrient uptake for a better functioning gut.

- Probiotics: Animals are shown to overcome heat stress and increase performance during the summer with the use of live yeast. The live yeast, which also improves fiber digestibility, promotes the production of fibriolitic bacteria, influencing the production of short-chain fatty acids.

- Beta glucans: When purified or included in mannan-oligosaccharides, they can increase the gene expression of mRNA to produce the proteins composing of tight junctions. This provides better integrity of the tight junctions, with less leaky gut and drier litter.

- Mannan-oligosaccharides: Mannan-oligosaccharides bind gram-negative bacteria, like E.coli or Salmonella, and gram-positive bacteria like Clostridium, better balancing the gut microbiota and improving feed efficiency.

- Pronutrients: These natural micro-ingredients act on specific cells by binding receptors that induce gene transcription. This activation leads to an increase in the RNA-protein translation rate and specific functional proteins are synthesized in the ribosomes with different effects depending on its target cell. For example, if these are enterocytes, the intestinal epithelium will regenerate faster, improving nutrient absorption while preventing micro-organism growth.

- Tannins: Tannins are bioactive plant extracts that can display a wide range of biological activities, contribute to improved gut health and offer an alternative to antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs). Low concentrations of several tannin sources have been shown to improve health status, nutrition and performance in monogastrics.

Ultimately, gut health is an animal welfare issue and the nutritionist’s role is to ensure the animal thrives with the help of its feed.

References available upon request.