Can we rely only on naturally occurring phosphorus in raw materials?

Feed phosphates have tripled in price in the recent months as a consequence of several factors, including the war in Ukraine, shortage in fertilizers, COVID pandemic logistic bottlenecks and rampaging inflation. One solution is to forget about supplementing feeds with phosphates, while relying on naturally occurring phosphorus in raw materials. But is this possible?

If we ask any supplier of feed phosphates, their answer will be, most likely, no. In contrast, all phytase suppliers will probably say yes. They will be both be doing their jobs, but where does this leave the rest of us? The answer, as usual, is somewhere in the middle. In practical terms, there are some feeds that can be formulated without any addition of inorganic phosphates and some others that cannot. This might appear simple, but the problem is to identify which feed falls in each category. So, let us first examine what is available from raw materials.

Ingredients rich in phytate phosphorus

Working only with poultry data, I had to rely on the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) book if only because the relevant U.S. National Research Council (NRC) poultry book is from the previous century, and it is always best to use an updated reference.

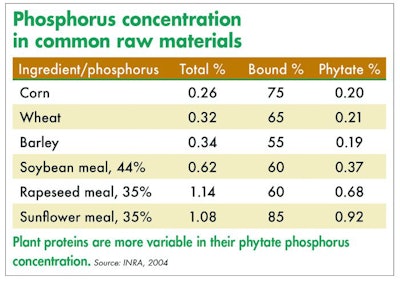

For this exercise, I selected three prominent cereals (corn, wheat and barley). Corn, because it is the main energy source in the Americas and many other parts of the world. Wheat, because it is a staple ingredient in Europe – and in short supply these days as wheat is not forthcoming from Ukraine. Barley, because it is used more than it is acknowledged.

I also selected three major plant vegetable protein sources (soybean meal, rapeseed meal and sunflower meal). The first is the main source of proteins for poultry and pigs, worldwide, whereas the second is quite important in northern Europe and in Canada (canola). Sunflower meal, again, is in short supply due to war in Ukraine – same situation as with wheat – and needs to be replaced. The following table gives information regarding total and bound-to-phytate phosphorus.

First, it is obvious that a typical corn-soybean meal-based diet contains about 0.20% to 0.22% phytate-bound phosphorus. Here, we are interested in the non-available phosphorus part because this is the substrate that the enzyme phytase will use to release phosphorus available to the animal. We could use other ingredients with more available phosphorus to begin with, but this is a different discussion as it entails the use of animal byproducts. For now, the main suggestion is to combine higher levels of the enzyme phytase with ingredients that contain more phytate-bound phosphorus than what is found in a typical corn-soy diet (about 0.20% in total).

Going back to the above table, we see that, in the case of cereals, the amount of phytate-bound phosphorus remains around 0.20%, and this is what the enzyme phytase must work with. Thus, changing cereals does not provide phytase with more phytate phosphorus. And, we should keep in mind that cereals make up 60%-70% of the final formula.

When we move to protein sources, we see a great difference between sources. Sunflower meal offers the greatest amount of substrate (phytate phosphorus) for super-dosing phytase. But we must keep in mind that protein sources make up only about 20% of the total formula. Although, on paper, rapeseed and sunflower meal look interesting, in reality, the difference is not that great.

As mentioned already, a typical diet with 70% cereals and 20% soybean meal contains 0.21% bound phosphorus. A similar feed with 20% rapeseed or sunflower meal contains 0.28% and 0.32% phytate phosphorus, respectively. Thus, the real difference is around 0.10% bound phosphorus that can be released with decreasing efficiency by increasing doses of phytase.

The biological limits of phytase

With a typical corn-soy diet, a single phytase dose releases about 0.1% (or 50%) of bound phosphorus, whereas a second dose will release another 0.05% for a total of 0.15%. Beyond that, it is doubtful if the economics justify mega-doses of phytase for miniscule gains in available phosphorus.

When dietary phytate phosphorus reaches higher levels (0.30%) or more, then adding a third dose of phytase has more substrate to act upon, releasing more phosphorus. This is an interesting proposition, as with certain ingredients (mainly bran portions of some grains), we can reach up to 0.40% phytate phosphorus. Whether it is economically feasible to try to release such phosphorus is a matter of discussion with each phytase supplier, but from a biological point of view, it is certainly feasible.

It should be noted, however, that no system in this universe (at least) is not 100% efficient. So, it is virtually impossible to convert all phytate-bound phosphorus into available phosphorus – some will always remain unavailable to the animal.

Redefining phosphorus needs

At the end of this discussion, it is reasonable to consider if the amount of already available, plus phytase-released phosphorus is indeed sufficient for meeting the needs of phosphorus for poultry. To this end, I must admit that our understanding of the actual needs is based on old data and extrapolation exercises, and some commercial experiences indicate that his might be feasible.

In practice, young animals (broilers) will need high doses of phytase along with high-phytate diets to cover their needs when we formulate diets without phosphates. Otherwise, we cannot meet their needs. On the other hand, finishing animals will satisfy their requirements even with corn-soy diets with or even without phytase, depending on the stage they are.

So, to answer the question of this article, in my opinion, it is possible to formulate diets for poultry without inorganic phosphates given we can satisfy their real requirements for available phosphorus. This is where we need to place more emphasis in determining these requirements with even greater accuracy.