The U.S. ingredient approval and review process is fraught with challenges, driving industry associations to push for revisions and improvements for bringing new products to market.

Feed industry members are calling for faster and clearer paths to bring new ingredients to market, while some advocate for the ability to add new claims to products.

An Informa PLC study, for the public charity the Institute for Feed Education and Research (IFEEDER), found that approvals for a new ingredient could stretch three to five years and cost more than $600,000. However, the American Feed Industry Association (AFIA) has been working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to cut the time involved and prompt revisions.

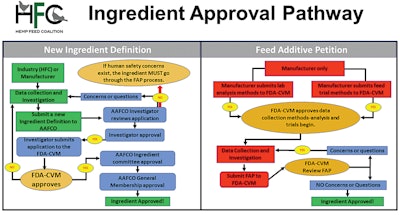

There are three methods for feed ingredients to be approved for use — gaining a new ingredient definition through the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO), developing an animal food additive petition (FAP) for the FDA or seeking to have products receive a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) notification.

The feed industry needs fair, efficient and predictable systems to bring new technologies and innovations to market, said Leah Wilkinson, AFIA vice president of public policy and education. “We want the three main review processes to continue to work.”

Improving the pathways could keep new products coming to the U.S market, she said. “It used to be that companies came to the U.S. first because they knew they could get through a review system. What was required was consistent, there were consistent review times and resources allocated to it, and it was more difficult to go through some of those other countries’ reviews — and now we’ve flipped that.”

“AFIA wants to get back to where the U.S. is leading in this effort and not being a follower,” she added.

Approval pathways background, highlights

FDA is the primary federal agency enforcing the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), making it responsible for regulating animal feeds, feed ingredients and additives, said Anne Norris, an agency spokesperson with FDA. Animal feed substances are related to “food” or having a nutritive value, taste or aroma, while an ingredient that makes a health claim, “affects the structure or function of the body,” or that can be used to prevent, or cure, a disease may be considered an animal drug.

Completing the FAP process requires that companies provide information documenting the use and safety of the ingredient, she said. The GRAS Notification Program is open to products that have gone through scientific analysis and review by qualified experts or that were used in animal feed before 1958.

A primary difference between the GRAS pathway and an FAP stems from where information is available, according to the FDA. Data used in a GRAS determination are “generally available,” while information informing an FAP can be privately kept and sent to FDA for review.

AAFCO manages the third regulatory pathway, the Feed Ingredient Definition Request Process. The voluntary membership organization includes local, state and federal agencies.

AFFCO generates the “model laws” and regulations used by most states and provides a way to create and implement “uniform and equitable laws, regulations, standards, definitions and enforcement policies for the manufacturing, labeling and the sale of animals feeds and ingredients,” according to FDA.

Before starting the AAFCO definition process, a company has to establish that the proposed use of an ingredient is safe, said Sue Hays, executive director with AAFCO.

“The proposed definition enters the AAFCO process when it’s already thoroughly vetted,” said Hays. Most often, if an ingredient is returned to a company for more information, it is because additional safety studies are needed, she added.

“The adoption of the ingredient definition by the AAFCO members … means that states will accept the ingredient in animal feed and pet food products,” she said. “Once the AAFCO membership votes to move a proposed definition from tentative to official, the industry can move ahead with using the ingredient in all U.S. states.”

Defining new ingredients with AAFCO

Currently, the Hemp Feed Coalition (HFC) is attempting to gain a definition for a new, hemp-based feed ingredient. As an organization and not a manufacturer, the coalition cannot apply for an FAP but can submit information on new ingredients for an AAFCO definition.

HFC is collecting data for an initial submission to gain approval for the use of hempseed meal and cake as a protein source in chicken diets, said Hunter Buffington, executive director of HFC. The application is set to be submitted to AFFCO for review and approval before moving to the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM).

The interest generated by the ingredient means that it may see a “fast-tracked” process, which could take about 18 months, instead of four years, said Buffington.

Funding has been a challenge as running trials and working with experts on the submissions can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, she said. “It’s incredibly expensive, and that’s per ingredient, per species — so over and over and over again, we have to meet those costs.”

“Once we get that hempseed meal and cake defined — so that ingredient is defined — then we prove safety and efficacy for the chickens,” she said. “The goal is to then move forward in developing the ingredient definition and gathering all this data for another byproduct or species.”

However, identifying all the information necessary for the submission has not been straightforward.

For example, HFC reached out to regulatory officials for guidance on inclusion rate, study length and animal numbers, while developing trials. “The response that I was given was to ask our principal investigator, which is really difficult. That’s like having someone telling you (that you) have to buy tickets for a show and then when you ask how to get tickets, they say, ‘We don’t know.’” Buffington explained.

The answer raised more questions when HFC started work on a beef cattle dossier because less research has been done in the U.S. with cattle and hemp than with poultry.

“Do we give them the minimum of information knowing they’re going to have more questions? Or do we try and anticipate their questions and provide more information than you normally would?” she said.

The path for taking potential feed ingredients to market can be long, convoluted and expensive. However, industry activists are pushing for reform and improvements to the process. (Courtesy Hemp Feed Coalition)

The path for taking potential feed ingredients to market can be long, convoluted and expensive. However, industry activists are pushing for reform and improvements to the process. (Courtesy Hemp Feed Coalition)Seeking GRAS determinations

Receiving GRAS designation makes feed ingredients more available for use at scale — especially for international feed production companies dealing with multiple sets of regulations, said Larry Feinberg, CEO and co-founder of KnipBio. The Massachusetts-based biotechnology company received its second GRAS approval for use of a single-cell protein feed ingredient in July.

Going through a regulatory process was the most effective way to make a new feed ingredient “universally adoptable” and improve its credibility, he said. “The beauty of going through the notification process with FDA was it got incorporated into the AAFCO definition that way.”

The company’s first dossier took about 15 months to navigate the review process once it was officially received, and the second review took a similar length of time. “There’s a systemic issue with the underfunding of these agencies — and it’s manifested in several ways,” Feinberg added.

A recommendation for companies interested in pursuing the path is to meet with the FDA and develop a relationship with the agency.

“Engage early, try and get their recommendations, and they’ve told you what to do,” said Feinberg. “You just don’t want to lose time because it’s already such a lengthy process.”

Feinberg said his other recommendation to companies navigating the GRAS process is to consider how their technology will develop when writing the submission: “Position your dossier in a way that can allow for improvement.”

Improving the process

AFIA has been advocating for increased funding for FDA’s CVM to reduce the time involved in the review process.

“That became our focus for that phase of what we were working on with the agency because they were down resources and they hadn’t been able to hire any replacements of people when people retired or left,” said Wilkinson.

“Getting FDA additional resources will make all three of those processes work more smoothly in the way that they are supposed to, and hopefully we can keep that … and get the industry back into that ability to bring products to market in a timely manner.”

Last fiscal year, the FDA received an appropriation to hire new employees. However, work to support FDA and update the approval process continues, said Wilkinson. “We got $5 million last year and we think they need $8 million, so we’re trying to ask for a little more so they can get a full complement of staff.”

AFIA also is seeking to change the statements that can be made about feed products, she said. “On the human food category side, they can make a lot of claims and say a lot about their products … and we can’t do that on the feed and pet food side.”

“We’re working on that topic internally right now and looking at the areas of health, structure-function claims, production claims,” she said. “That alone could also help break up some of the issues that we’ve had with ingredient reviews and the time frames because we have a lot of ingredients that don’t fit very neatly into that taste, aroma, nutritive value box but yet they are fed to an animal.”

The inability to make those claims about feed ingredients may put U.S. ingredient manufacturers at a competitive disadvantage as they can be made in other countries.

“We feel like we should be able to modify our regulatory system in order to bring those products to the market in a safe manner,” she said.