Diet composition, along with meal size, frequency and timing, influence performance of the sow and her piglets

Genetic and management developments have resulted in sows producing larger litters. This means longer farrowing times, increasing the importance of energy availability for sows in late gestation. Larger litters also influence colostrum and milk availability for each piglet. Attention should be paid to fiber level, energy availability and feed intake for each stage.

A sow uses 36.6% of her body mass a year to develop her piglets, and 200% to produce milk to feed them. It is important to consider not only diet formulation but inherent feeding behavior to manage feeding for optimum health and performance of both the sow and her piglets.

Sow dietary decisions should relate to requirements in different phases: gestation, parturition, lactation, etc. Nutritional requirements and feed intake should both be considered, while functional nutrients and additives can also play an important role.

-

Genetic improvements

While improving productivity and efficiency is positive for the industry, it means that feed formulators and producers need to adapt their strategies. In 2000, the average litter size was 12 to 14 piglets and by 2018, it was greater than 16. “Management and nutrition changes for hyperprolific sows are essential for optimal productivity,” said Bruno Silva, professor at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, in Brazil. “Genetic selection also means more teats.”

If the teat number increases from 16 to 18, nutritional requirements for both the fetus and the mammary gland increase considerably. Experiments have estimated this increase to be 13 to 16% for metabolizable energy (ME) and 14% for standardized ileal digestible (SID) lysine.

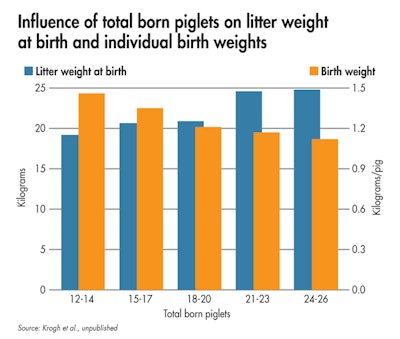

Using Danish breeds as an example, Dr. Uffe Krogh from INRA, France, evaluated trends in sow productivity: “From 2009 to 2019, the total number of piglets born has increased by 0.3 per litter per year. When comparing litter weight at birth with total number of piglets born, litter weight is 5.6 kilograms higher in litters of 24 to 26 piglets compared to those of 12 to 14. Despite the increase in litter weight, birth weight of the individual piglet is 340 grams lower per pig in the largest compared to the smallest litters.”

Despite the increase in litter weight, birth weight of the individual piglets is lower per pig in the largest compared to the smallest litters. (Krogh et al., unpublished)

Despite the increase in litter weight, birth weight of the individual piglets is lower per pig in the largest compared to the smallest litters. (Krogh et al., unpublished)-

Changing requirements with parity

Despite weight losses after farrowing and increases following weaning, sows continue to grow up to their fourth parity. This means that their requirements change whether they are gestating or lactating, but also as they become older. They have a higher metabolic weight, require less fat but more protein and their feed intake reduced. Diet formulation, meal size and frequency should all be tailored to the parity of the sow.

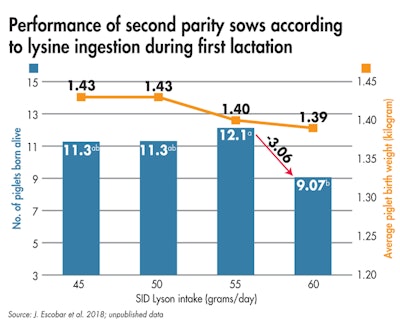

Because nutrition in each lactation period is important for sow performance in subsequent parities, whether higher or lower than optimum, the amount and ratios of nutrients influence productivity. For example, those sows with the highest lysine intake during lactation had a lower number of piglets born alive from the following pregnancy. The ideal ratio should be 3.2 g SID lysine per 1,000 kcal of ME, according to recent work.

Sows with the highest lysine intake during lactation had a lower number of piglets born alive the following pregnancy. (J. Escobar et al. 2018; unpublished data)

Sows with the highest lysine intake during lactation had a lower number of piglets born alive the following pregnancy. (J. Escobar et al. 2018; unpublished data)-

Dealing with hunger during gestation

Hunger impacts feeding behavior. However, it has been shown that feeding more than once a day doesn’t affect the reproductive performance of sows. Instead, the volume of feed has a greater effect on cortisol levels, an indicator of stress. Low feed intake increases levels, which in turn has a negative effect on birth weight. Nevertheless, there are natural variations influenced by gestation stage and parity order.

Feed efficiency is also affected by low feed intake. Prolonged fasting time activates hepatic gluconeogenesis, where free amino acids are redirected for energy synthesis and ratios become unbalanced for optimum performance.

Satiety depends on glycaemic level, feed is just a vehicle for providing the nutrients required to meet targets for each gestational phase. Energy requirements are dynamic, varying on a daily basis throughout gestation. Similarly, the required ratio of amino acids varies throughout gestation (2.36-3.09 Lys SID/ME kcal).

-

Energy for parturition

Larger litter sizes lead to longer farrowing times, a factor that is thought to increase the number of stillborn piglets. It takes on average 24 minutes to give birth to each piglet, so there can be up to 14 hours between the birth of the first and last piglet. The energy demand for this process can be seen in the respiration rate of sows, which is around three times higher during farrowing than in a normal state.

Energy from starch is taken up from the stomach and small intestine, with glucose levels peaking around an hour after feeding. But farrowing is a marathon, not a sprint, so a slower release of energy is required. This was illustrated in a series of experiments where, when the number of hours from feeding to onset of farrowing was above three, the length of the farrowing process increased following the pattern of peak and decline of glucose uptake from feed.

Trials have shown that providing more fiber reduces the number of stillbirths by providing slower release energy for the process of parturition. Scientists have recommended supplying 500 grams of dietary fiber a day, within around three kilograms of feed a day split over three meals. Increasing dietary fiber in late gestation has the additional benefits of reducing constipation and increasing water uptake.

Sow diet decisions should relate to the different requirements during gestation, parturition and lactation. (Countrypixel | AdobeStock.com)

Sow diet decisions should relate to the different requirements during gestation, parturition and lactation. (Countrypixel | AdobeStock.com)-

Colostrum production

Colostrum intake influences pre-weaning mortality, particularly for low birth weight piglets. With more piglets, the amount of colostrum available to each piglet is lower, so to maximize production feed intake around farrowing shouldn’t be reduced below 3 kg. However, it is interesting to note that 80% of the fat and lactose for colostrum is synthesized after the onset of farrowing. Increasing the energy available to sows in late gestation also increases colostrum yield, in turn benefiting piglet weight gain in the first 24 hours.

Providing more dietary fiber, as an energy source, may improve colostrum production, an area requiring more research.

-

Milk production

Larger litters have an increased demand for milk, making an adequate energy and nutrient supply essential. Unlike for gestation, feed consumption during lactation should be maximized for optimum sow productivity. Nutritional requirements are based on feed intake, which differs between herds, breeds, as well as individuals over the lactation period. Some sows will eat the optimum amount, but others eat significantly less, which affects their potential milk production.

There is also a complexity in the efficiency of energy use for milk production — 13% is lost in the conversion of ME from feed into milk. Often a sow’s energy intake doesn’t match their requirement. Therefore, body condition and nutrient intake should be carefully managed to optimize litter performance.

-

Gut function

This critical area of pig nutrition still a hot topic and worthwhile consideration. Dr. Helle Laerke from Aarhus University, in Denmark, explained that “increasing the dietary fiber level increases the number of butyrate-producing bacteria in the cecum and also improves satiety.”

When diets were supplemented with 15% of alfalfa, genes involved in short-chain fatty acid absorption and satiety were upregulated. Further work looked at how higher fiber levels delayed gastric emptying and the appearance of glucose.

Sows have changed both physically and in terms of production potential. Producers need to think about their feeding behavior and not just how they manage feeding. Research has demonstrated that it is possible to influence farrowing performance, colostrum and milk production by nutritional changes. There is an increased importance of energy during a longer farrowing process, so meal frequency and size — as well as body condition — should be optimal. Increasing fiber levels cannot only improve satiety, but also provide a slower release of energy. Similarly, there is an increased demand for colostrum and milk, for which energy and nutrient ratios should be tailored to parity.

Editor’s note: This article presents information from Adisseo’s Poultry and Swine conferences, held in Paris in October 2019.