Experts: Managing feed costs with US$14 soybeans is possible, but requires out-of-the-box solutions

The agricultural world had no shortage of economic turmoil when 2020 began. African swine fever continued to rage in Europe and Asia, and then COVID-19 cut a similar path across the globe, making its way to the Americas and shutting down factories, shipping lines and, eventually, meat processing plants. Yet in the midst of it all, one thing the world did not have a shortage of was soybeans.

For the first half of the year, soybeans sold for less than US$10 per bushel and seemed quite stable, recalls Fernando Caja Del Prado, a purchasing manager at Nutreco‘s Nanta Group. Farmers entered the year with a glut of unsold beans leftover as a result of the U.S.-China trade war, and the weather seemed to foretell another year of high crop yields.

Fortunes began to change after the August derecho raised the specter of crop damage and, by September, prices began to climb. But the real game changer came when China suddenly began to buy corn and soybeans far in excess of any previous prediction.

“A lot of us didn’t see this coming,” says Hans Stein, a professor of animal science at the University of Illinois. “This is just bad luck and some circumstances we didn’t know would come, and therefore things have turned out the way they have.”

By early 2021, soybean prices exceeded US$14 per bushel and corn surpassed US$5.50, pushing many farmers, according to a February report, to seek out less expensive alternatives or even food-grade grains.

With high prices for critical ingredients across the board, there is little animal producers can do to avoid high feed prices entirely, according to Ester Vinyeta Punti, global nutrition manager for Nutreco. But there are strategies that can be employed — immediately and long term — to reduce some of the financial pain.

Ingredient swaps

When producers face abrupt increases in ingredient prices, the quickest solution, according to Stein, is often swapping the high-priced ingredient for something similar but affordable. The trick to this, he says, is that the best options will vary considerably based on one’s location.

Rice bran, for example, might be a good alternative for producers in Missouri or Arkansas with ready access to a rice mill, but in Illinois or Iowa, hauling the rice bran north could prove cost prohibitive. In the Midwest, producers often turn to distillers’ grains to replace soybeans, but with the decreased demand for ethanol due to the pandemic, distiller’s grains are hard to come by. An alternative to the alternative, Stein says, might be corn germ meal or corn gluten feed from a wet milling facility.

The corn gluten recommendation comes with a caveat, Stein says: The quality can be highly variable.

For unreliable ingredients like corn gluten, or any unfamiliar feed ingredient, Stein says, it’s important to collect a sample and conduct a nutritional analysis. Without this, the nutritional content of the entire diet could be thrown off balance; you can’t just take one ingredient out and swap it for another and assume everything will be fine, he says.

Another effective strategy, Stein says, is to look for waste products available from human food processing. Bakery meal, he says, is such a good ingredient that companies have sprung up to collect leftover bread and cereals, strip them of their packaging, and resell them to animal producers.

“Some people have even been able to buy dog food that is off spec and cannot be used for dogs,” Stein says, “but can be used for pigs.”

These kinds of opportunities tend to come and go, Stein says, so taking advantage of them requires developing long-term relationships with local mills or brokers who can flag, for example, a batch of dog food that got recalled because it was mislabeled.

A final option, if producers are really struggling to find suitable ingredients in their area, is to blend old, dirty or even contaminated grain with better-quality feedstuffs.

“If the mycotoxins are not too high and you can clean it very well,” Stein says, “you may be able to blend it down and mix in clean corn.”

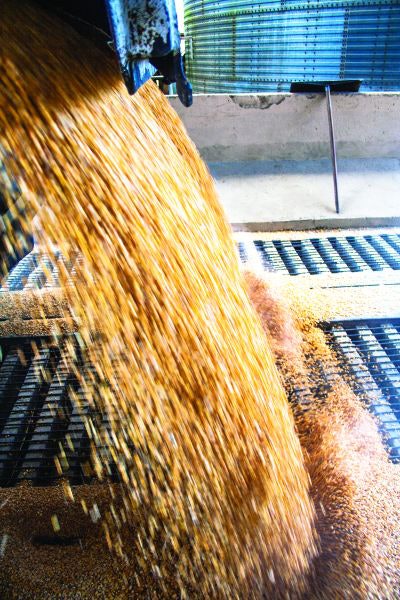

With commodity prices rising, experts note that alternative ingredients aren’t the only option for reducing costs. (Alfribeiro | iStock.com)

With commodity prices rising, experts note that alternative ingredients aren’t the only option for reducing costs. (Alfribeiro | iStock.com)Alternative ingredients

Alternative ingredients can help with shot-term price hikes, but they’re usually a temporary solution at best, according to Bart Borg of Standard Nutrition.

“Alternatives to soybean meal and corn travel in lockstep on price with soy and corn,” Borg says. “Those selling those ingredients are aware that if they’re a substitute to corn and corn has doubled in price, they can now double their price.”

For most alternatives, Borg says, there is a brief window of opportunity where the alternative is truly a solution to high prices. But that window may last a month or less before alternative prices catch up with conventional ingredients and, in the case of 2021, he says, the ship for most alternatives has already sailed.

There are, however, price coping strategies that do not rely on alternative ingredients, but on milling and husbandry practices.

One of the first solutions he employs, Borg says, is to check the particle size of his feed.

“The finer the grind, the better the digestibility, so every pound that you buy goes further and the animal is getting more out of it than if you have whole corn or very course particles,” he says.

Unfortunately, no study has shown that grinding soybeans will improve the digestibility of the amino acids — the solution there, according to Borg, is probably crystalline amino acids. For improving energy efficiency, he says, the only downside to downsizing your particle size is that feed flow can become a problem in automatic feeders.

“If you’re using an automated system, my suggestion is to keep trying to get your corn finer until you find that you need to tap on the bin to get it to start flowing,” he says. “Then back off a bit. Make it a little more coarse so it will flow.”

Particle size, Borg says, also matters for producers who use pelleted feeds, which means times of high ingredient prices are also good times to check your mill’s processing standards.

Managing feed safety and quality is also especially important during times of high ingredient prices, according to Roland van Dalen, marketing manager for Selko Feed Additives. Pathogens that may enter feed products may consume nutrients, decreasing feed efficiency and, should an animal become sick, the illness may interfere with its ability to absorb nutrients.

In addition to good mill management, Stein says producers may find it worthwhile in the long term to expand their grain bin capacity. With more bins, he says, producers are better positioned to take advantage of opportunities to pick up cheap quality feedstuffs they can store away for times of economic uncertainty, even if those ingredients are outside the standard fare like corn and soybeans.

“Having more different bins is important,” he says. “If you want to be able to take advantage of whatever opportunities come your way, you have to have those bins.”

Another area Borg says he has experimented with in his own animals is optimizing diets for price performance, rather than maximum growth.

“In times of high feedstuff costs, you need to stand back and … realize, ‘I’m going to lose a little bit of average daily gain and feed conversion may go up,’” Borg says, “but the savings on those ingredients may be greater than what your loss is.”

The one production management strategy Stein does not recommend is culling or cutting herd numbers to reduce feed consumption. There are signs this is happening, he says, but in the long run, it rarely works out for the producer who adopts this strategy because by the time they reap the imagined cost savings, prices have changed — including, often, the market price for pork or poultry.

“Usually trying to jump in and out of the market, you mistime it, has been my experience,” he says. “I don’t think I would advise that. It’s a risky strategy, jumping in out of the market.”

Forward contracting and staying on top of commodities markets is also an important long-term strategy for mitigating financial risk, according to Paul Bertels, principal economist for Farm Gate Insights. While this latest round of price increases may have caught many off guard, there were early signs of trouble with nations such as Ukraine and Russia taking steps to curb grain exports in early 2020. Producers who felt caught off guard shouldn’t beat themselves up too badly, he said, because prices rose over a very short period of time. But it was possible to see this coming, he said, and highlights the need for producers to pay attention to international markets besides major producers like the U.S.

“To put it in economic terms, the U.S. is the residual supplier of grain,” Bertels said. “We are the world’s grain storage. As we saw dramatically this year, when everyone else is out [of grain], they come running to America because we’re usually not out.”