Extrusion is most commonly associated with pet food and aquatic feeds; however, in livestock feed manufacturing, extruders produce many of the same results as a pellet mill, only through a different process.

According to Spencer Lawson, UP/C technology manager with Wenger Manufacturing Inc., extruded feeds offers several advantages over pelleting, including less feed waste, reduced ingredient segregation, increased nutrient density, increased digestibility and decreased microbiological activity.

As antibiotic reduction and elimination becomes more prevalent in animal production, feed manufacturers and nutritionists can utilize extrusion to ensure feed safety.

At the 2018 FIAAP Animal Nutrition Conference, Lawson discussed how extruders produce pathogen-free feed while allowing formulators to utilize beneficial feed additives and less expensive raw materials to improve animal health and performance.

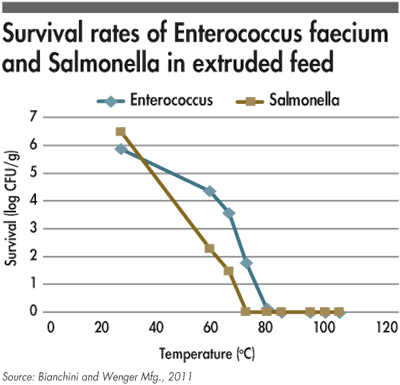

Salmonella and Enterococcus faecium are eliminated from extruded feeds produced at 27.5 percent moisture, processed at 70 to 80 degrees Celsius. Because extruders operate at a much higher temperature than pellet mills, feed producers can ensure the elimination of pathogens in their animal feed. | Source: Bianchini and Wenger Mfg., 2011

Promoting health through processing

The elimination and reduction of antibiotics in animal feed slows the development of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and eases the economic burden of formulation costs.

According to Lawson, there are several steps to consider when producing a specific feed for the animals that are consuming it:

- Formulating a diet with a proper nutrition profile while excluding additives that are not heat labile

- Pasteurizing and pelleting a foundation, hygienic feed for a short time at a high temperature

- Stabilizing the shelf-life of the feed by controlling water activity through post-pasteurization unit operations

- Enrobing the final feed pellet by precise application of heat-labile additives, such as probiotics and enzymes

Once the base or foundation feed/pellet is produced, it is possible to begin thinking of the next step: coating and/or enrobing.

Maximizing coating’s potential

As feed formulators turn to feed additive alternatives — probiotics, prebiotics, organic acids, enzymes, etc. — to combat common pathogens in livestock production, one must consider whether they will remain stable when faced with severe processing temperatures.

“Moisture and temperature might accelerate sensitive ingredients in breaking down — which is exactly what we don't want to happen,” Lawson says.

It can be difficult to control this with certain types of extrusion. However, livestock feed-specific extruders exist that offer a shorter resonance time in the barrel as compared with conventional extruders. In short, a process that exhibits an elevated temperature for a short time is utilized.

According to Lawson, fats and oils can be included in the formulation, by being pumped continually in the pre-conditioner at levels up to 7 percent before noticing a negative impact on pellet quality. This is due to the fact that pellets are formed by agglomeration versus pressing layer after layer of feed much like a pellet mill. Beyond that, there is room for an additional 6 to 7 percent of fat/oil absorption during atmospheric coating. The reason: the pellet is “melting” into its final state, with the materials agglomerated into one piece versus several layers.

“By having an open, porous structure, it allows you to post-coat with feed additives that may not survive the extrusion process,” Lawson says. “Now the enzymes, probiotics and other heat-sensitive ingredients that you might not want to consider — or maybe over-formulate if they are heat labile — can bind to the feed and make it much more efficient.”

“When we talk about producing feed without the use of antibiotics, we still want to try to deliver the most hygienic, pasteurized feed possible,” Lawson says. “If we are producing feed from anywhere from 100 to 140 degrees C, we are definitely eliminating anything that can be harmful to the flock or the herd.”

References available upon request.

Editor’s note: The 2018 FIAAP Animal Nutrition Conference, co-located with VICTAM, was held in Bangkok in March 2018.