The emergence of deoxynivalenol (DON) and zearelanone (ZEA), the two main Fusarium toxins, have garnered renewed interest and attention in Europe. Today, an increased vigilance is needed for cereals from diverse sources as they can be heavily contaminated by these toxins. It is also important to be alerted regarding their adverse effects on animals, and of course, to understand how to design an effective counteraction strategy.

European survey reveals high levels of DON and ZEA

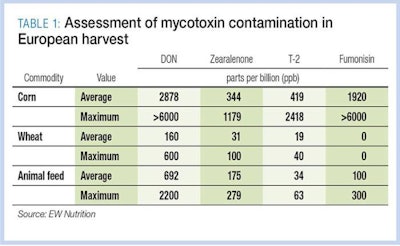

The results of the European samples from the third quarter of 2014 (Table 1) revealed elevated loads of DON and ZEA obtained from samples of cereals and complete feeds from customers around the globe.

Although these mycotoxins are more or less always present in samples from Europe, their levels are very high in the current harvest. Regarding DON, 30 percent of the corn samples were quite heavily contaminated, with levels above 3,000 ppb. These DON levels reflect in animal feed where the average is above 650 ppb and several samples had levels above 2,000 ppb, relatively high loads compared with the EU guideline of 8,000 ppb for corn; 900 ppb for pig feed and 5,000 ppb for poultry feed.

In contrast lowest levels — in fact zero detectable DON concentration — was observed in 40 percent of the wheat samples.

A similar pattern as in DON can be seen with ZEA: 30 percent of the corn samples are contaminated with more than 500 ppb. Acceptable levels, according with the EU, are 100 ppb in feed for piglets and gilts and 250 in feed for sows and fattening pigs, contrasting with 2,000 ppb in corn. Corn can account for up to 50 percent of the feed; therefore, even when the mycotoxin levels in the cereal seem acceptable, precautions be taken so the feed does not overpasses the EU guidelines.

Although the sample pool is relatively small, DON and ZEA are in rise in Europe. As both mycotoxins are produced mostly in the field by the Fusarium molds, their high levels can be explained by the warm and rainy conditions during autumn in Europe.

DON in pig and poultry diets

Pigs are very sensitive to feed contamination with DON. The previous name of DON was vomitoxin and this reflects its most obvious symptom, vomiting. Pigs consuming diets exceeding 20,000 ppb DON will show this symptom, and at 12,000 ppb DON pigs will refuse to consume the feed after the first intake. It is believed feed refusal and vomiting are due to interference of DON with the peripheral and central nervous systems. In breeding sows, levels of up to 3,500 ppb DON cause reduced fetal development, but sows are more resilient and appear to overcome a mild toxicity as they produce eventually normal offspring. Of course, higher levels will reduce feed intake, as in growing pigs, and this will cause problems during pregnancy and lactation.

At lower concentrations, starting from 600 and up to 2,000 ppb DON, feed intake and weight gain are reduced. In some studies, feed intake reduction was observed with only 350 ppb DON in complete feed. In general, a no-effect level of 300 ppb is recommended by experts, whereas 1000 ppb might be more practical in terms of balancing performance and profitability. Currently, the EU guideline level for DON in pig feeds is 900 ppb, when it is the single mycotoxin in the feed.

Poultry, and particularly chicken, are not as sensitive to DON as pigs. Studies with 9,000 ppb DON appeared to cause some organ damage; however, 5,000 ppb DON revealed no damaging effects. Experts recommend that chicken feeds should contain no more than 2,500 ppb DON, while current EU regulations call for maximum DON concentration at 5,000 ppb in complete feeds for poultry as a single mycotoxin.

ZEA in pig and poultry diets

While DON appears to be more prevalent in corn, ZEA is more frequently encountered in other cereals, although they both infect all cereals but at variable degrees. This mycotoxin is very stable during feed processing and storage, and as such it remains a persistent problem to the feed and animal industry. In fact, a survey (2003) found ZEA in one-third of more than 5,000 samples tested across Europe.

Exposure to feed contaminated with ZEA disrupts normal reproductive functions because this mycotoxin has a very strong estrogenic activity. Developing gilts are considered the most sensitive farm animals to ZEA contamination. ZEA binds to estrogen receptors in the uterus and mammary glands, and also affects cells on the bones, brain, and the immune system (immune-toxicity). The consequences are false heats, heat returns and swollen vulvas on gilts, increase of the uterus size, atrophy of ovaries, decrease in pregnancy rates, mummifications, premature births and abortions in reproductive sows. As ZEA can be excreted in the milk, piglets may also be affected. Boars may show lower levels of testosterone with the consequent loss of libido, lower sperm quantity and decreased sperm quality.

In poultry, ZEA has similar effects. In laying and breeding hens, it reduces egg production and lowers egg and eggshell quality, causes early sexual maturity, increases embryonic mortality and causes infertility in females and males.

Interactive effects

Although these two mycotoxins appear to work through different mechanisms, their combined presence may give ground for a synergistic negative effect. In a feeding study, the combined effects of DON and ZEA in pigs were studied by varying the amounts of ZEA (up to 6,000 ppb) in diets contaminated with increasing levels of DON up to 5,000 ppm. As expected, ZEA contamination, did not alter feed intake, weight gain, or feed efficiency, but it causes reproductive organ alterations. In contrast, DON clearly decreased feed intake and growth, but it did not affect reproductive organs. There was an indication of a greater reduction in feed intake caused by DON when ZEA was present (P = 0.08).

When the organism is burdened by several mycotoxins, further toxicity increases damage due to the inability of the liver to detoxify all mycotoxins. The magnitude of this negative additive effect most likely depends on the overall mycotoxin burden.

How to combat DON and ZEA contamination

The first measure against any mycotoxin contamination is awareness that such problem is real and very possible to occur at any time. This is especially true when cereals or feed are sourced from a variety of suppliers, often across a large geographic region. Secondly, it is always a good investment to implement a robust survey system where samples of incoming raw materials and feeds are routinely analyzed for mycotoxins.

It pays off to use the correct anti-mycotoxin agent in feeds that contain mycotoxins at levels considered enough to cause even subclinical toxicity. This will ensure that animals remain healthy and grow at maximal rates and reproductive animals remain fully productive throughout their life.

As a final precaution, although it is routinely recommended to add a mycotoxin binder or neutralizer to counteract mycotoxins, we often bypass the fact that at least a small part of mycotoxins escapes luminal binding and enters the organism. When this happens, liver damage is very likely, the more so when feeds are heavily contaminated. As documented by numerous studies — and also evidenced by human clinical studies and practice — using a liver protecting agent helps in reducing these damaging effects. Such an agent is silymarin, a natural plant extract that is frequently used in cases where liver regeneration is required. Studies have shown that animals fed diets supplemented with silymarin, as part of an integrated anti-mycotoxin strategy, withstand much better the effects of mycotoxin contaminated feed.

In conclusion, measures should be taken in animal production in order to minimize the damaging effects of the current contaminations. Sampling and monitoring is essential as well as choosing the best strategy to counteract the effects of the mycotoxin loads in animal feeds.